01

I was a Chinese Internet addict: a tale of modern medicine

01

I was a Chinese Internet addict: a tale of modern medicine

I was a Chinese Internet addict: a tale of modern medicine

by McKenzie Funk

First published in Harper's Magazine, March 2007

I had read online about the Chinese Internet-addiction clinic, but I didn't know if it would accept me until I was actually there. The clinic was run by Chinese doctors and soldiers in a two-story block of concrete on the heavily congested grounds of the Beijing Military Region Central Hospital. Its entrance was a sloped hallway lined with inspirational posters: images of winding highways, palm-fringed swimming pools, empty beaches lapped by tropical waves. Flora, a film student who'd agreed to be my translator, read the captions as we walked in. "Overprotection will make your children disabled," she whispered. "Courage has unbelievable power."

A squat woman with blackened front teeth and a lab coat was standing expectantly in the waiting room. She wore white running shoes with Velcro fasteners, and her hair was cut into a tight bob that faded into a mullet. She smiled warmly and introduced herself as Dr. Yao. I thanked her for seeing me.

"How long do you go on the Internet each day?" she asked. I stared into space. "That would be, average, uh, eight to twelve hours," I said. "Sometimes less."

"What do you do on the Internet?"

"I read the news a lot. The New York Times online—every story. All of Google News, at least everything that's interesting. The Washington Post. Sometimes I send messages to friends and other people. Sometimes, when I have to buy an airline ticket…"

"Do you play Internet games?"

"No. I just talk to friends and read. But I've watched cartoons on cartoon sites, and I look at things I could buy online."

"Do you have anxiety when you can't get on the Internet?"

"I do wonder if I'm missing messages from friends—emails I really should be reading—and I wonder about the news. Maybe there's a story, American politics or something, and every hour I want to know what's changed. When I have the opportunity, I check those things, and it feels better."

"How old are you?"

"Twenty-nine."

I explained that my girlfriend, Jenny, was half Chinese, and let Dr. Yao assume that this had something to do with my being here. I said that Flora was a friend of Jenny's cousin and was helping me on behalf of the worried family. This was a lie.

A nurse in a pink cap walked by, then a soldier in camouflage fatigues. A girl of twelve or thirteen passed next, waving an exuberant good-bye to Dr. Yao while her father toted her suitcase. On the wall of the waiting room, I noticed, was an illustrated poster explaining the inner workings of computers: the Windows operating system, a Web browser set to Google, the interface of the popular Chinese chat program QQ.

"Do you have the ability to take yourself away from the Internet?" Dr. Yao asked. If I had to go to dinner with someone, I could go, I said. But I was often late.

She asked if I had other compulsive behaviors. I admitted that I sometimes read magazines all the way through from the front page to the back page, and that I felt compelled to watch movies, even bad movies, to the very end. She asked if "small things" got stuck in my head, if I often stayed up all night, and if I thought about the Internet while doing other activities. "It's not the Internet itself that I think about but the things inside it," I said.

I was led to a small room furnished with a pullout futon and a gray computer. The hallways were empty; the director and most of the patients, Dr. Yao explained, were at the set of Tell It Like It Is!, one of the oldest and most famous of China's talk shows. She seated Flora and me in front of the computer. Its desktop image was a field of blooming flowers with characters that read, "I really want my psychological health."

On the computer was a diagnostic test. Dr. Yao said there were ninety statements, and I was to rate their truth on a scale from A (not at all true) to E (very true). She helped me fill in my biographical details—level of education, date of birth, profession (I said I had none)—then left Flora and me in private.

"You have headaches," the computer offered. I chose "B." "You get agitated." I chose "C." "When you have headaches, your head is filled with unnecessary thoughts and words." I pondered the necessity of my thoughts. "C" again. "You feel dizzy or faint," the computer continued. "You have less desire for the opposite sex. You have no desire for food. You check things again and again. You hear things others cannot. You feel that others control your mind. You can't control your temper. You blame your troubles on others. You blame yourself. You are forgetful. You feel lonely. You feel scared. You feel bored. You feel sick. You feel irritable. You cry easily. You worry about your appearance. You worry too much. You can't fall asleep. You have a hard time breathing. You feel your brain is empty. Your heart beats too quickly. You have chest pain. You are afraid of open spaces. You want to smash things. You think about death. You want to end your life. There is something blocking your throat."

I lied outright only a few times: claims of lethargy, lack of appetite, indifference to sex, and isolation from others. I managed a sort of exaggerated honesty, sticking at least to the contours of the truth. If a statement merited a "B," I might give it a "C." But an "A" was always an "A," an "E" always an "E." None of the ninety questions mentioned the Internet, and after an hour the test was done.

A new doctor, younger and much taller than Yao, with fine features on a narrow face, came in with a printout of the instantaneous results. I received decent marks for anxiety, depression, interpersonal communication, and hostility-nothing over what the doctor said was the threshold, 1.50. But my level of paranoia was worrisome: 2.00. Worse was my obsessive-compulsive rating, 2.20. "This is bad," the doctor said. Toward the bottom of the page was a number that seemed out of place: 60. I asked what it signified. She didn't hesitate: "That means you're an Internet addict."

That afternoon, I sat in Dr. Yao's office, looking at translations of Alfred Adler, Carl Jung, and Sigmund Freud as she asked about my successful father and mother and my history of small colleges and good grades. Two doctors, both men, strolled by carrying a pirated DVD of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, which they started watching in the room where I'd taken the ninety-question test. I signed a release authorizing the treatment and paid Dr. Yao 2,100 yuan, enough for the first four of the twenty days I was asked to stay.

I retreated into my new room, #27, and listened to the clatter of feet in the hall: my fellow patients, back from their television appearance. At 9:00 P.M. there was a rap on the door. A nurse came in, handed me seven pills, and waited. One was a red gelcap, another a chalky white half-capsule. Four were small white tablets, and a fifth tablet was red. I put the pills in my mouth, hid them in my cheek, and pretended to cough. She kept staring, so I filled a paper cup with hot water from a thermos and drank. When I realized I'd accidentally grabbed two cups that were stuck together, I used my tongue to make a space between them and spit out the rapidly dissolving pills. I crumpled the cups and tossed them into the trash. The nurse didn't seem to notice. She flashed a proud smile and returned to the hall. I was left with the sinking feeling that I'd swallowed the chalky half-capsule and spent the rest of the evening trying to figure out if I felt dizzy, if something was wrong in my head.

It was a dark season for the Internet users of China. Just weeks before I checked in, during the holiday marking the fifty-sixth birthday of the People's Republic, one of their own was killed. Her screen name was "Snowly," and she'd been playing the online game World of Warcraft nonstop for days on end, preparing to join her guild of fighters against the black dragon Nefarian. She collapsed from exhaustion and died in real life before the virtual mission could succeed. Two dozen warriors held her virtual funeral a week later. They kneeled in the digital grass and bowed their heads as words of remembrance floated off toward a range of jagged virtual peaks.

In Shanghai, a court sentenced forty-one-year-old online gamer Qiu Chengwei to life in prison for the murder of a fellow player. It was a complicated case: Qiu had lent his cyber-weapon, a "dragon saber" that he'd won in Legend of Mir II, to a younger player named Zhu Caoyuan, who in turn had sold it for $870 and kept the money. Enraged, Qiu went to the police, but they couldn't help him; China had no laws protecting virtual property. So Qiu broke into Zhu's one-room apartment while he and his girlfriend slept, and Zhu barely had time to put his pants on before Qiu stabbed him in the heart with a real knife.

The number of Chinese Netizens (the preferred translation of the term wangmin, literally "network citizens") recently surpassed 130 million: the world's second-largest online population, after America's, and growing at 30 percent a year. Broadband is cheap, fast, everywhere; Internet cafes number in the tens of thousands; all-night passes cost as little as 5 yuan, or about 60 cents. At any given moment, more than 2 million Chinese are battling one another in virtual worlds, and at one record-breaking moment 22 million users logged on to the chat and social-networking portal QQ. Last year China's online gaming industry posted revenues of $670 million—up 45 percent from 2005, when Netizens spent more than $12 billion on Web access.

Chen Tianqiao, the thirty-two-year-old CEO of Shanda, distributor of Legend of Mir II and other multiplayer games, had recently become a billionaire--one of only ten in the country. Another billionaire was William Ding Lei, who founded NetEase.com. Yahoo! injected a billion dollars in cash into the e-commerce site Alibaba.com, and China Mobile announced that it had spent more than a billion dollars in two years to bring Internet and phone service to 25,862 rural villages.

Cracks appeared everywhere. Bloggers such as Sister Hibiscus, Rascal Swallow, and Stainless Steel Mouse were vaulted to awkward, inappropriate levels of celebrity. A server crashed after 50,000 people simultaneously tried to download twenty-five minutes of lovemaking sounds from online sex diarist Muzi Mei. A new kind of sweatshop appeared in cities up and down the coast: warehouses packed with young Chinese who played Mir II or World of Warcraft in twelve-hour shifts, winning virtual gold and weapons that rich foreign gamers would buy with real money. A song called "Mice Love Rice," which had been posted online by an unknown lounge singer and music teacher named Yang Chengang, became a national mantra: "I love you, loving you/As the mice love the rice."

Fueled by QQ, a culture of one-night stands infested urban centers. Girls logging on after midnight were barraged by instant messages. "ONS?" they asked. "ONS?" Meanwhile, role-playing Netizens began registering for wanghun (cyber-weddings) and raising digital children together. Hundreds of thousands of strangers engaged in the fantasy at sites such as Virtual Family, and real-life courts granted divorces to real-life spouses as the online bigamists were exposed. Some 30 percent of marital troubles in Guangzhou were said to be caused by virtual affairs and marriages.

In November 2005, a 22,500-person, thirty-city study by the China Youth Association for Network Development confirmed what everybody in China already knew: one out of every eight Chinese young people was an Internet addict. This was followed by the even darker news from the Chinese Academy of Sciences that 80 percent of college and university dropouts had failed due to Internet addiction. A respected Beijing judge, Shan Xiuyun, reported that 90 percent of the city's juvenile crime was Internet-related. In Hunan Province, Internet-related crimes were said to be increasing by 10 percent every year.

In Jiangxi Province, a computer-science major rendered penniless by his addiction killed a homeowner in a burglary gone awry. In Chongqing, a train crushed two middle-school students who'd fallen asleep on the tracks after forty-eight hours online. In Lanzhou, the story was told of a fourteen-year-old who killed his great-grandmother with a brick to the head, took 390 yuan from her body, and went to spend it at an Internet cafe.

Also in Shanghai, it was reported that a young man who'd played online games for six years would be stuck forever in a sitting position. His back was fused at a 90-degree angle; doctors said there was nothing they could do. In Tianjin, a thirteen-year-old played World of Warcraft for thirty-six hours in a row, then rode the elevator to the top of his twenty-four-story building and jumped. He left behind an 80,000-character diary about the virtual world and a suicide note saying he was off to meet the game's characters. His parents sued World of Warcraft's distributor for 100,000 yuan.

Perhaps more remarkable than China's crisis was the response: mass shutdowns of illegal Net cafes, regulations that now kept them 200 meters from any primary or high school, national addiction help lines and "safe surfing" programs, and a thirty-eight-episode anti-Internet addiction sitcom, The Story of Shan Dian Mao. The clinic was part of an all-out counterattack by a people who were certain they saw a danger that the West, in its more incremental steps to modernity, largely hadn't. It is normal for humans to become lost, to drop out of society, and perhaps just as normal for them to lose themselves but tell themselves they're fine. It is rarer, I thought, when we dare name the culprit.

The next morning, I awoke in the fetal position in my hospital bed, shivering underneath a Winnie-the-Pooh comforter. It was 6:40 A.M. My room was cold and dark, and I could barely make out the Pooh poetry on my matching beanbag pillow: "When the/twinkly stars/fill the pretty/night sky,/they all wave/good-bye/with a smile/and a sigh." Another patient, a mustachioed fifteen-year-old, was standing over me. "Time get up," he said. "Hurry, hurry." I stepped into the hallway, where eight bleary-eyed teenagers were lined up against the wall, standing rigid, as a young man in military camouflage examined them. I was the last in the lineup; they'd already been waiting ten minutes.

The soldier was known as Xiaohei, or "Little Black," a nickname that distinguished him from our other minder, the older but shorter "Big Black." His skin was dark, his uniform perfectly starched. Little Black was over six feet tall, lean and muscular, with spiky hair and a face oddly reminiscent of the action hero The Rock. He was the perfect role model.

Little Black led us through a wing where adult alcoholics were packed three to a room, wearing wifebeaters and tattoos while chain-smoking in bed with the television blaring. Once outside, we began to jog. We ran counterclockwise around an enormous new outpatient building, passing hedges trimmed in the shape of a small intestine and a crowd of old people practicing tai chi in a courtyard. One patriotic red banner after another stretched across the road: "We have no weekends so we can create a harmonious society," the first said. After the last banner—"Concentrate on work, speak the truth, try real things…and you'll achieve"—we raced each other for 200 yards to our workout zone, a basketball court. I came in fifth.

Our first exercise was a stretch that started with fists together and ended with one arm raised in a triumphant, Travolta-like pose. We repeated it eight times, first with the left arm up, then the right, counting in English for my benefit. We then approximated a circa-1996 raver's invisible-ball dance, in order to loosen our wrists. We did twenty pushups in unison. We spread our arms like wings, seemingly for balance, and did twenty squats. Off to the side, a minuscule seventeen-year-old patient worked on his own program. His name was Qin Xiangzong, and he was here in part because he had tried to stab a fellow cadet at his officers' academy. The boy soldier put his hands on his waist and kept his feet planted in one spot, then gyrated wildly as if swinging an imaginary hula hoop. He stared intently at the ground, unable to make eye contact with anyone, his face fixed in a demented grin.

Basketball, when it got going, was not a team sport. No one passed; everyone charged toward the goal alone. There were two air balls and six shots off the rim before any went in. My teammate Hu Yimao, a fifteen-year-old with spiky Rod Stewart hair, double-dribbled every time he got the ball. If he pulled down a defensive rebound, he threw up a shot immediately, never mind whose basket he was under. But the game was more unpracticed than unathletic, and the boys took it seriously. My team, aided by a slightly older patient named Su Xu—who dressed in black pants, a black shirt, and black, Japanimation-style cut-off gloves-and a tall, thin boy from Xian, He Cong, won 26 to 7. Our opponents dropped to the ground and did another twenty pushups.

I ate breakfast—bread and a watery rice sludge—alone in my room, and at 9:00 A.M. a beaming Dr. Yao came in to give me my medicine. I used the same double-cup trick. Ten minutes later, the door opened and a man wheeled in a cart. Atop the cart was a device the size and shape of an old dot-matrix printer but with wires connecting it to three jumper cable-like calipers and six small, color-coded suction cups. He had me lie down on the bed, lift up my shirt, and stretch my arms above my head. He swabbed an area abutting my right nipple with alcohol and affixed the red suction cup. The other five cups—purple, yellow, green, blue, and brown—were placed around my heart after further swabbing. He clamped the calipers around both wrists and my left ankle, and after that I wasn't allowed to move. He leaned over the machine. I had no idea what he was doing. I gritted my teeth and genuinely expected a jolt of electricity—I had heard that the doctors would send 30-volt shocks to pressure points on the most recalcitrant patients—but I never felt a thing.

Barely eight months old, the clinic was already famous—the subject of glowing coverage by CCTV, the China Daily, and the state-run Xinhua News Agency. Since it opened in March 2005 on the grounds of the military hospital, its all-army staff had helped hundreds of patients. It claimed a cure rate of 80 percent, a phenomenal degree of success that was attributed to the expertise of the clinic's founder, Tao Ran, who'd been treating various addictions for twenty years. The clinic was often full, and plans were under way to expand it from 20 beds to 150.

It was not cheap. At 410 yuan a day, about $50, a typical twenty-day stay was equivalent to the average city dweller's annual salary. Food was an extra 30 to 50 yuan a day if you ordered Chinese takeout rather than suffer hospital fare—which we all did—and gym access was 15 yuan a day. Every patient left a 200-yuan deposit in case he decided to break something. But the steep price bought a comprehensive program: a cocktail of abstinence, forced basketball, weight lifting, daily sessions with a therapist, oral and intravenous drugs, and, for extreme cases, the aforementioned 30-volt electric charges.

The condition being treated at the clinic did not, according to Western medicine, officially exist. But it was not without advocates back home. The first paper on Internet addiction was presented in 1996—soon after the birth of the Web itself—at the American Psychological Association's 104th annual meeting, in Toronto. Its author, Dr. Kimberly S. Young, proposed that the disorder be diagnosed using modified criteria for pathological gambling. Addicts were those who answered "yes" to five of eight questions:

1. Do you feel preoccupied with the Internet?

2. Do you feel the need to use the Internet with increasing amounts of time in order to achieve satisfaction?

3. Have you repeatedly made unsuccessful efforts to control, cut back, or stop Internet use?

4. Do you feel restless, moody, depressed, or irritable when attempting to cut down or stop Internet use?

5. Do you stay online longer than originally intended?

6. Have you jeopardized or risked the loss of a significant relationship, job, educational or career opportunity because of the Internet?

7. Have you lied to family members, therapists, or others to conceal the extent of involvement with the Internet?

8. Do you use the Internet as a way of escaping from problems or of relieving a dysphoric mood?

Young, who runs the website www.netaddiction.com and a practice in Pennsylvania, was bolstered in her controversial work by Connecticut psychologist David Greenfield and Harvard's Maressa Hecht Orzack, who run www.virtual-addiction.com and www.computeraddiction.com, respectively. In his 1999 book, Virtual Addiction, Greenfield underscored the hidden danger of the Internet's "endless boundaries and unending opportunity." He described the satisfying sensation of a process without close, "the principle of incomplete Gestalts." The Internet was an echo chamber, Young believed. Like drugs or alcohol, it could magnify existing problems—"as the alcoholic's marriage gets worse, drinking increases to escape the nagging spouse, and as the spouse's nagging increases more, the alcoholic drinks more."

One of the most rigorous investigations into Net abuse was led by Dr. Nathan Shapira of the University of Florida and published in 2000 in the Journal of Affective Disorders. He tentatively classified it as an impulse-control disorder, like kleptomania or trichotillomania (the irresistible urge to pull out one's own hair): an increasing feeling of tension or arousal before logging on, nearly impossible to fight, followed by a pleasurable release.

But whether it was called Internet Addiction Disorder (IAD), Pathological Internet Use (PIU), Impulsive-Compulsive Internet Usage Disorder (ICIUD), Maladaptive Internet Use, Excessive Internet Use, or Netomania, the condition was denied an entry in DSM-IV, the West's gold-standard manual of mental illnesses. The case for a new classification was muddy. By treating the vast Internet as a monolith-something to be addicted to rather than through—researchers ran into definitional hurdles. Was someone with an online-porn problem an Internet addict or just a pornography addict who indulged via the Web?

Skeptics argued that people lost themselves in socially acceptable diversions (books, television, jogging) all the time: The major difference, they claimed, was bias against the Web. And Shapira's research, consisting of face-to-face psychometric evaluations of twenty subjects, found that so-called addicts had a raft of other mental problems: More than half of the people in his study were determined to be manic-depressive; 60 percent had anxiety disorders. Fifteen of twenty had been treated with psychotropic medications; nineteen had a history of mental illness in the family. On average, each subject had five major psychiatric issues.

Before arriving in Beijing, I'd had my own theory about China's addicts. I hadn't been to Beijing in nine years. I'd pictured a peasant nation susceptible to the dazzle of technology, suddenly come from the fields and into the Internet cafes, and figured that the addicted Netizens were attracted to the Internet's novelty—taken in by newness itself. As a Westerner steeped in modernity, I was largely immune. By this logic, China's crisis was a Gods Must Be Crazy parable, with the Netizens playing the role of the Bushmen, the Internet the role of the Coke bottle. But the longer I spent in the clinic, the less this explanation made sense to me.

My companions were Netizens, but more precisely, I found, most were jiaozhu (kung fu masters)—people who played Internet games all night and slept all day. The best gamers among them were zhanshen: giant heroes in war. For them, the first hurdle here was simply to adjust to the 10:00 P.M. lights-out, when a doctor's hand would reach through their door and flick off the switch. New arrivals were often sedated with a clear IV fluid and left for twenty-four hours until their sleep cycles normalized.

The business of "calming the brain and correcting hormonal imbalances," as Dr. Yao put it, was done by a different IV fluid, a maple syrup-colored sedative of unknown provenance. I was the only patient who didn't receive the sedative daily, because upon check-in I'd pleaded with Dr. Yao to keep the needles out of me. I had an honest phobia. "Once I had a knee problem," I'd told her, "so they took a blood test and they stuck a needle in me and I watched all the blood drain into a bag."

The boys told me that the sacks of sedative took half an hour to drain—longer if one was better hydrated—and left them feeling lethargic, dizzy, and extremely thirsty. One showed me the eight needle holes clustered near the wrist on the top of his hand. My new friend Zhang Dong—the mustachioed boy who'd woken me up and spoke the most English of any of them—had eleven holes. It was like counting rings in a tree: he'd been at the clinic eleven days.

Dong told me I was lucky because I'd been assigned to his psychologist, Dr. Xu, the best the clinic had. "He has a Ph.D.," Dong said. "He will ask you lots of questions about private, very, very personal things." I replied that I was ready—but this was only partly true. I'd never seen a therapist before, and I've never been one for much introspection.

I soon learned that I was the only patient who used email, who didn't play online games, and who didn't have a chat account. But this was unremarkable: While I was in China, Guo Liang of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences published a study showing that only two thirds of Net users had email accounts, and only a third of them checked their email on a daily basis. Forty-two percent of Netizens did not use a search engine. Seventy-five percent had never made an online purchase.

Instead of replacing encyclopedias, newspapers, storefronts, travel agencies, and the U.S. Postal Service, Chinese people—both addicts and non-addicts—seemed to be replacing the television with a more interactive way to entertain themselves. This was not the business-oriented Web of the West. Guo's study explained that Chinese people overwhelmingly used the Internet to chat, play games, download music, and read about celebrities. The Web lives of the Netizens—whose QQ profiles featured not photos, as on MySpace, but personalized avatars wearing clothing and jewelry bought in a digital store—had very little in common with their real lives; they went online to escape.

The question of how Netizens became kung fu masters had lately taken a surprising turn: instead of looking at what they were escaping to, researchers dared ask what they were escaping from. The man asking the toughest questions was Professor Tao Hongkai, an historian who'd returned to China from the United States in 2002 in order to retire. In May 2004, he'd decided to invite high schooler Qu Qian, a top student turned addict whom he'd read about in his local newspaper, to his house for ad-hoc therapy. He'd cured her in a miraculous nine hours. Word got out. He began receiving phone calls day and night. Mothers sent letters, some written in their own blood, begging for help. Soon he was treating other teenagers, hundreds of them, for free; he packed thousand-seat lecture halls in seventy cities in twenty provinces in sixteen months. His method: actually talk with—not to—the child, and actually listen.

The professor's explanation of Chinese Internet addiction amounted to an indictment of Chinese society. He railed against the one-child policy and the xiao huangdi (little emperors) it had created: children whose every material need was met even as spiritual needs were ignored. Instead of having hopes of their own, spoiled teenagers carried those of six other people--their parents and two sets of grandparents. They were overprotected but underdeveloped, without discipline or a sense of meaning. "They have nothing to hold on to," he said. "They are empty inside."

He believed an even bigger problem lay with China's intensely test-based academics: a child's entire scholastic path—in some ways his or her life—could depend on one exam, the gaokao, the sole criterion for college entrance. The pressure was crushing; peers became competitors; teachers became slave drivers. Students had time only for rote memorization—not for singing or volleyball or after-school fun, otherwise defined.

Professor Tao noticed that Mir II and World of Warcraft were games not of gore but of wits and teambuilding and winnable battles. He ventured that they gave teenagers something society, and especially schools, did not: freedom. "If they want to fight, they can fight. If they want to curse, they can curse. If they want to marry, they can marry." Back in real life, he said, "every child is like a little donkey. The teacher grabs his two long ears and pulls and pulis. The parents get behind him and push and push." I thought about my life in America. A little push didn't sound so bad.

I had my psychotherapy sessions in the afternoons. Dr. Xu was soft-spoken but direct, and he had a habit of pausing dramatically before every question. When I gave an answer, he'd raise his eyebrows and say, "Hmmm," then scribble notes on his clipboard. I tried to be honest. Dr. Xu asked about my parents—did I love them, did I respect them, did I live up to their hopes?—and about problems with Jenny, which I said had contributed to my addiction. "Is there such a thing as true love?" he wondered. "Do you think true love must have two sides? Can you truly love someone who doesn't love you back?" I said it was possible. You could fall in love with someone's potential.

Dr. Xu discovered I'd been a philosophy major in college, and he asked me abruptly what the meaning of life was. I didn't know. It was something more important than being happy, I said. "If you had just seven days left to live, what would you do?" he asked. I threw out an awkward answer about going home to my parents in Oregon and writing letters of farewell—not because I was trying to keep in character but because I didn't want to think honestly about death and had no idea what I'd do. "Why don't you and your father talk about feelings?" he asked.

He had me draw a picture of a house, a picture of myself, and a picture of a tree. My house had a chimney and a window and a mailbox; my tree had pinecones like the evergreens in my parents' back yard. But it was ungrounded, I later noticed—no base and no roots, just a trunk floating in space. Dr. Xu didn't believe me when I said I rarely remembered dreams after waking up, but it was true; I rarely do.

The boys always filled my room once he left. The grungy, ten- by twenty-foot space, with its three mismatched chairs, TCL brand television, ceiling hook for an IV drip, and yellow fake flowers, was becoming the clinic's social nexus. Dong, who one winter had protested being cut off from the Internet by hanging himself upside down from his parents' balcony, shivering violently with spittle dripping from his mouth, was my most frequent visitor. He told me he'd once stayed online for seven days in a row. A lanky, easygoing boy I called Sam (he reminded me of a friend's brother), whose online record was four days, often joined him.

The first time the pair came over, Dong immediately stared at the television as if something was amiss, then leaned over and turned it on for me. "Okay?" he asked. A boy with a blue-striped sweater and slicked-down hair that made him look like a drowned cat, Song Zhixuan, also appeared. He leaned against the doorjamb because he was too shy to enter, and a few others came all the way in. They took over the bed and chairs and began discussing the relative merits of. Beijing and Shanghai. "Beijing is bigger," Dong said. "Shanghai is," said Sam. "Beijing." "Shanghai." "Beijing." "Shanghai." "Beijing!" "Shanghai!" "Beijing!" "Shanghai!" I was the first foreigner any of the boys had met.

Another time, when we were alone, Dong told Flora and me about the Tell It Like It Is! television appearance with Director Tao. It had not gone well. With the boys at his side, Tao had been arguing against Shanda CEO Chen Tianqiao about Internet addiction. At one point, Tao invoked one school of Confucian philosophy: that human nature is essentially good. Something odd happened. The boy soldier, the would-be stabber, ran to the middle of the stage and began to argue against Tao, point by point.

"There's nothing unhealthy about playing Internet games!" he squeaked, standing as tall as he could in his cadet uniform. Due to his small size, he said, classmates in the real world had done violence to him for the last seven years—they'd tortured him, laughed at him. He spoke for ten minutes, telling the crowd that the only true philosophy was that of Xunzi, a Confucius disciple who came to believe that man was essentially evil: "One is born with feelings of envy and hate, and, by indulging these, one is led into banditry and theft." After the boy soldier was done, the Tell It Like It Is! host said he had an urge to hug him. He did so. Director Tao didn't get to finish, and the crowd had seemed to side with the Shanda CEO, who'd employed an argument some have made to keep Internet misuse out of DSM-IV: today's "addicted" Netizens were like the people transfixed by television in its early days—this was nothing more than a honeymoon period—and their obsessions would subside.

Dong tapped his feet and crossed and recrossed his legs as he told us about the boy soldier's outburst. He rubbed his hands together and rolled his head back and forth, blinking constantly. "He is very extreme, very extreme," he said. "When he attacked his classmate with a knife, it took six soldiers to restrain him." I asked if he believed what the boy soldier said about human nature. "I agree with Director Tao," Dong said, "but sometimes people do evil things for no reason—like in 1999, when America bombed our embassy in Belgrade for no reason."

He told us he had prepared a speech of his own for Tell It Like It Is! but never had a chance to share it. During the Qing dynasty, he said, there was a famous official named Lin Zexu who had stood up to British opium importers. Lin confiscated 20,000 chests of opium and destroyed them; he barred British ships from trading in the ports of Canton. He also sent a letter to Queen Victoria:

We find that your country is sixty or seventy thousand li from China. Yet there are barbarian ships that strive to come here for trade for the purpose of making a great profit. The wealth of China is used to profit the barbarians…By what right do they then in return use the poisonous drug to injure the Chinese people? Even though the barbarians may not necessarily intend to do us harm, yet in coveting profit to an extreme, they have no regard for injuring others. Let us ask, where is your conscience?

Lin's patriotic acts precipitated the disastrous first Opium War, in 1839, but earned him an honorable place in history. Now Chen Tianqiao and his company, who had profited greatly by importing Legend of Mir II from South Korea and were soon to bring an online Dungeons & Dragons from America, were the barbarians. "They are criminals," Dong had planned to say, "and Director Tao and his comrades are like Lin Zexu—the heroes of the nation."

As the days passed, I came to understand the essence of the doctors' fight. It was to make our actual lives more real than our virtual lives—to show that it was most fulfilling to be engaged in a world, however imperfect, that had a physical existence. It was a constant struggle. One afternoon, Little Black and Big Black took us to the nearby Power-House Gym, five stories up an office tower of blue glass and polished marble, where Dong and I galloped side by side on walking machines at 13 kilometers an hour. The other boys played Ping-Pong. The soldiers themselves ignored us; they were immediately engrossed in the computers at the gym's four-PC Net cafe. After an hour, Little Black stood up and began rubbing his eyes and slapping himself in the face. We got ready to leave, but Big Black stayed glued to his computer. We walked back without him.

But we were learning the lesson even if they were forgetting it. We learned to face the challenge of standing like real soldiers, keeping our knees perfectly straight and our heads perfectly straight and our shoulders back and our hands flat at our sides. We felt the real pain of sets of thirty, then forty push-ups. We practiced folding our Pooh blankets in the military's "bean curd" style—the ideal was a perfect, tofu-shaped block—until each of us mastered the art. We hung out in the hall sometimes, the wonderful Dr. Yao watching over us like a mother hen, laughing, asking us questions. We got used to conversation, used to caring about what others had to say, used to having others care about what we had to say.

We learned about consequences. The Rod Stewart wannabe and his thin friend from Xian sneaked off to a store during one morning's run and filled their pockets with 10-yuan packs of Beijing Cigarette Factory filter lights. Little Black patted them down, found the contraband, and made them do a hundred push-ups--then forced them to stand perfectly still for five minutes in the middle of the basketball court. The same day, Dong wandered into my room with a plastic soda bottle, shook it vigorously, and idly opened it. It exploded. He learned to mop.

"Everyone has psychological barriers," Dong declared after one of his injections. "For the people here, the barriers are just bigger." He sat in the blue chair that had become his usual perch. The shy boy in the blue-striped sweater, who'd finally gotten up the courage to come inside and discuss Internet games, sat on the bed. He smiled awkwardly and draped an arm over Sam in a show of camaraderie. Dong admitted that he'd sneaked through the clinic at night and tested every computer—none of them had Web access. Do you know "Mice Love Rice"? he asked me. "Mice love cheese," I said. He and Sam played a version of "paddy cake": "One, two, three, four, we'll play Internet games no more."

The boys were half my age, but I began to feel like one of them. One morning, Dong got a text message from a friend at the prestigious Gansu Province high school he'd dropped out of. The friend was in the midst of an English test; I was a native speaker. We rushed out an essay for him—the topic was "rules of the library"—and texted it back, experiencing the thrill of sticking it to the bigger world. We laughed like idiots. "My classmates study fifteen hours a day," Dong said. "School is corrupted," said Sam.

I wanted to go home, so after four days at the clinic, I set an alarm on my cell phone, and when it began ringing, I pretended to answer a call. I told Dr. Yao that it had been Jenny—that she'd found a treatment center for me in Pennsylvania and booked me a flight departing the next morning. I could be closer to her but still receive help. Dr. Yao seemed sad for a moment, but she understood. "We will support whatever is good for you," she said. I began to feel guilty. Dr. Yao was a kind woman, and I'd stopped believing that her cure was so far out of proportion to China's crisis. When she tried to return the money I'd overpaid—a few hundred yuan—I donated it to the clinic.

The boys were shocked at my departure. We posed for photos: me with Dong, me with the boy soldier, me with black-clad Xu, me with the shy boy in the blue sweater, me with Rod Stewart, me with Sam and bunny ears, me with Sam and no bunny ears. I went into the hall and took more photos with Little Black and Dr. Yao and the nurses. I met Director Tao for the first time, and he sat with me as his staff's cameras flashed. "You studied philosophy," he said. "Chairman Mao was our greatest philosopher, so I'll give you this." It was a gold Mao pin in a red box.

I was allowed a final meeting with Dr. Xu. "Did you have any dreams last night?" he asked. I actually remembered one: I'd dreamt that I'd lied to Dong and the others about my real age, and that I'd been caught; they'd realized that I wasn't one of them just as I'd begun to think that I was. Dr. Xu brought up Heidegger and Sartre, and I had to reveal how embarrassingly little I remembered from my college studies. He flipped through his notes, which had become so thick that they fell off the clipboard. He looked me in the eye. "You are looking for some advice, I think." I was. "Read Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus." I still haven't. He asked me to do a story stem: he'd start the story, and I'd finish it. "Imagine that you're a small tiger walking alone in a tall forest," he said. For a moment, however fleeting, I truly did.

Radio interview:

02

Opinion: Deciding Where Future Disasters Will Strike

02

Opinion: Deciding Where Future Disasters Will Strike

Opinion: Deciding Where Future Disasters Will Strike

By McKenzie Funk

First published in the New York Times Sunday Review, November 2012

We all have an intuitive sense of how water works: block it, and it flows elsewhere. When a storm surge hits a flood barrier, for instance, the water does not simply dissipate. It does the hydrological equivalent of a bounce, and it lands somewhere else.

The Dutch, after years of beating back the oceans, have a way of deciding what is worth saving with a dike or sea wall, and what is not. They simply run the numbers, and if something is worth less in terms of pure euros and cents, it is more acceptable to let it be flooded. This seems entirely reasonable. But as New York begins considering coastal defenses, it should also consider the uncomfortable truth that Wall Street is worth vastly more, in dollar terms, than certain low-lying neighborhoods of Brooklyn, Staten Island and Queens—and that to save Manhattan, planners may decide to flood some other part of the city.

I think I was the only journalist who witnessed the March 2009 unveiling of some of the first proposed sea-wall designs. “Against the Deluge: Storm Surge Barriers to Protect New York City” was a conference held at N.Y.U.’s Polytechnic Institute in Brooklyn, and it had the sad air of what was then an entirely lost cause. There was a single paying exhibitor—“Please visit our exhibitor,” implored the organizers—whose invention, FloodBreak, was an ingenious, self-deploying floodgate big enough to protect a garage but not at all big enough to protect Manhattan. When we lined up for the included dinner, which consisted of cold spaghetti, the man waved fliers at the passing engineers. But as I look back over my notes, I can see how prescient the conference was. A phrase I frequently scrawled is “Breezy Point.”

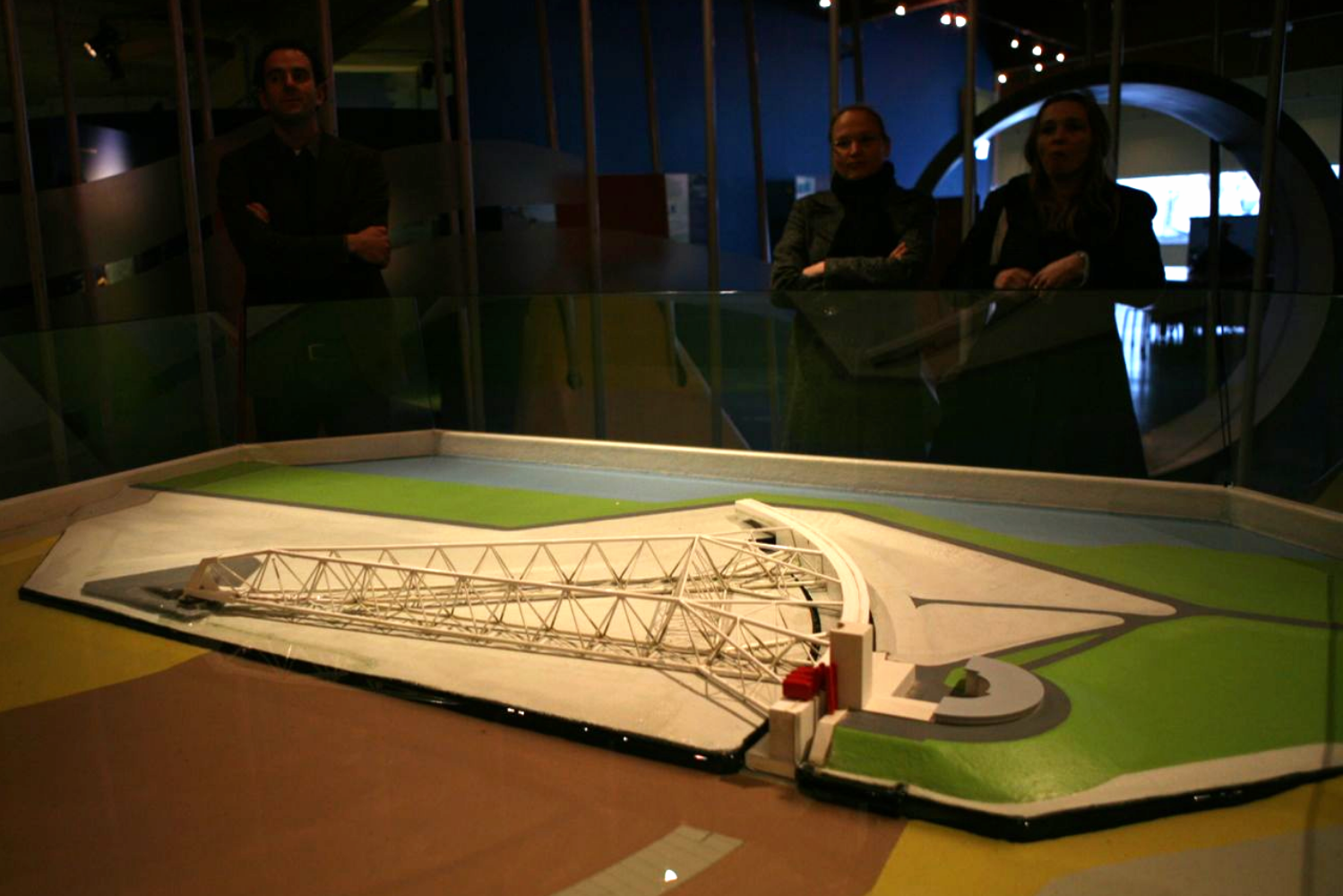

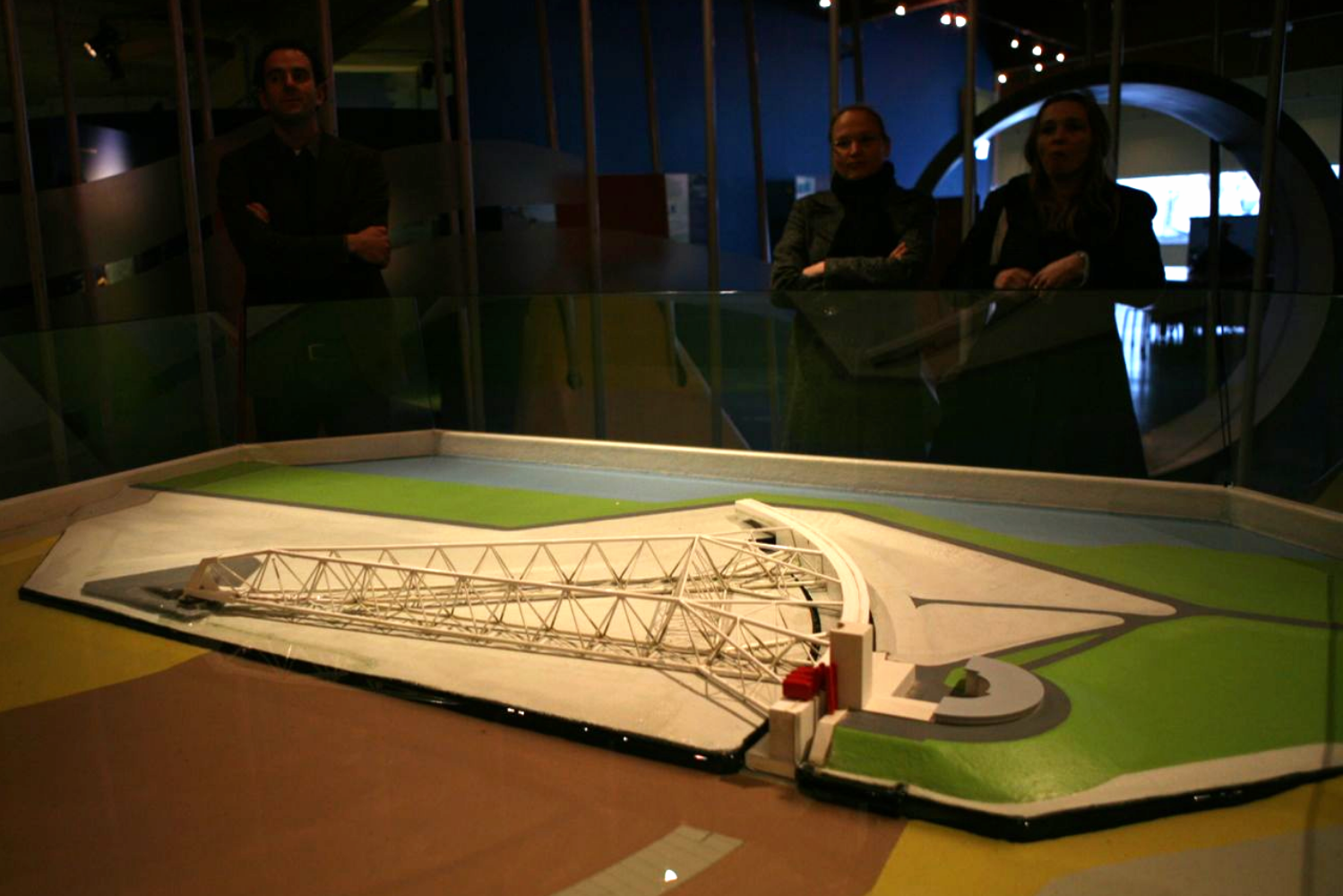

One speaker got a sustained ovation. He was an engineer from the Dutch company Arcadis, whose $6.5 billion design is one with which I suspect we will all soon be familiar. It is a modular wall spanning 6,000 feet across the weakest point in New York’s natural defenses, the Narrows, which separates Staten Island and Brooklyn. Its main feature is a giant swinging gate modeled on the one that protects Rotterdam, Europe’s most important port. Consisting of two steel arms, each more than twice as long as the Statue of Liberty is tall, Rotterdam’s gate is among the largest moving structures on earth. And New York’s barrier would stretch across an even larger reach of water—“an extra landmark” for the city, he said triumphantly. That’s when everyone began clapping.

The engineers in the room did not shy away from the hard truth that areas outside a Narrows barrier could see an estimated two feet of extra flooding. If a wave rebounding off the new landmark hits a wave barreling toward it, it could make for a bigger wave of the sort that neighborhoods like Arrochar and Midland Beach on Staten Island and Bath Beach and Gravesend in Brooklyn may want to start fretting about.

I attended the conference not just because I was interested in the fate of New York, my onetime home, but because I was recently back from parts of Bangladesh decimated by a cyclone. By now it is commonplace to point out that climate change is unfair, that it tends to leave the big “emitter countries” in good shape—think Russia or Canada or, until recently, America—while preying on the low-emitting, the poor, the weak, the African, the tropical. But more grossly unfair is the notion that, in lieu of serious carbon cuts, we will all simply adapt to climate change. Manhattan can and increasingly will. Rotterdam can and has. Dhaka or Chittagong or Breezy Point patently cannot. If a system of sea walls is built around New York, its estimated $10 billion price tag would be five times what rich countries have given in aid to help poorer countries prepare for a warmer world.

Whether climate change caused Sandy’s destruction is a question for scientists—and in many ways it’s a stupid question, akin to asking whether gravity is the reason an old house collapsed when it did. The global temperature can rise another 10 degrees, and the answer will always be: sorta. By deciding to adapt to climate change—a decision that has already been partly made, because significant warming is already baked into the system—we have decided to embrace a world of walls.

Some people, inevitably richer people, will be on the right side of these walls. Other people will not be—and that we might find it increasingly convenient to lose all sight of them is the change I fear the most. This is not an argument against saving New York from the next hurricane. It is, however, an argument for a response to this one that is much broader than the Narrows.

03

Gitmo on the Radio

03

Gitmo on the Radio

First aired on Too Much Information and The Story, May and July 2011

A conversation with a man from Tajikistan who was detained in Pakistan, questioned, and eventually flown to Guantanamo. After two years, he was released—and he speaks with journalist McKenzie Funk about his time in prison.

04

The Man Who Has Been to America: Four prisons. Three countries. Two years. One Guantanamo detainee's story.

04

The Man Who Has Been to America: Four prisons. Three countries. Two years. One Guantanamo detainee's story.

The Man Who Has Been to America: Four Prisons. Three countries. Two years. One Guantanamo detainee's story.

by McKenzie Funk

First published in Mother Jones, September 2006

In the enemy combatant's house, in the room where he eats and prays and sleeps, a single window casts its light on a single adornment: an enormous Soviet-era map of the world. It is the first thing I notice after I arrive unannounced one cold fall morning and am ushered into the warmth of the room. We sit on the floor below an elongated Africa, a tiny America, and a colossal, pink-shaded U.S.S.R. A brother with a prosthetic leg appears and lays out a brightly patterned sheet still covered with past meals' bread crumbs. Non ham non, nonreza ham non, the Tajik proverb goes: "Bread is bread, crumbs are also bread."

The enemy combatant serves the tea. He pours it before it's properly steeped, dumps the watery cups back into the pot, and repeats. If he's unhappy to see an American after Guantanamo, he doesn't show it. He smiles, and two wrinkles appear on his left cheek. I ask him his full name. Muhibullo Abdulkarim Umarov, he tells me. He says he is 24 years old. He asks, "You want to know the story of my capture, yes?"

The village of Alisurkhon, where Umarov was born and eventually returned, is a collection of mud-walled homes and apple orchards beneath the 14,000-foot peaks of Tajikistan's Pamir Mountains. Physically, it's closer to Afghanistan than to the Tajik capital, Dushanbe, 12 hours and 150 miles of dusty, nauseatingly potholed road to the west. Along with post-communist detritus that litters the roadside—smokestacks, rusting tractors, half-finished cities of concrete and rebar—are occasional burned-out tanks, leftovers from the 1992-97 civil war that killed up to 150,000 Tajiks after the breakup of the U.S.S.R. The crumbling infrastructure disappears as you climb higher into the Pamirs; the frequency of gutted tanks increases. This valley along the Obihingou River was once home to the Islamist opposition, and nearly a decade after the peace accords, the ex-Soviets who control Dushanbe still believe they have enemies lurking here. It is a suspicious place to be from.

The valley has a wild-boar problem. The hogs are everywhere lately, trampling crops, tearing through fields of potatoes and wheat. Local hunters, increasingly orthodox since the fall of the Soviet Union and no longer interested in eating pork, have stopped controlling their numbers—and Russian hunters have stopped coming here altogether. Aid groups, wary of the valley's growing conservatism, have largely steered clear. When a friend and I visited on a mountaineering trip in the summer of 2003, villagers said we were the first Westerners they'd seen in 12 years.

I'm back in the Obihingou Valley a year and a half later when one of these villagers, a bearded farmer with a toothy grin and two missing fingers, tells me about Umarov. We're having fried potatoes and soup in the farmer's guest room, a converted shed with whitewashed walls and plastic bags for windows. "There's a man in the valley who has been to America," he mentions casually. I find this unlikely. "Really. He was in a prison. They made a mistake." He begins to chuckle—that America could make such a mistake amuses him. I ask where the prison was. "Koba...kaba?" It takes me a moment to realize he's trying to say "Cuba," and a few days to cancel trekking plans and find an ancient Uaz jeep to transport me down to Alisurkhon.

We sit cross-legged in Umarov's room, circled around the teapot, me staring at the wall and running a tape recorder, Umarov staring out the door. The brother with the prosthesis—Ahliddin —keeps shuffling in and out, and my friend Kubad (he asked that his name be changed for the purposes of this story), a Tajik mountain guide playing the role of translator, sits with us as well. Umarov looks mostly at Kubad when he answers questions, keeping his hands in his lap, speaking so softly that it sometimes seems he's whispering.

"As you know, 1994 was a year of continual war in Tajikistan," he begins, "and the planes came to bombard our village. I was 14. Ahliddin was 10." The boys were in the field outside their grandparents' home when one of the bombs fell, and day turned to night, so thick was the dust in the air. "My brother's right leg was amputated from the knee down," Umarov says.

In this same house, under the same Soviet map, he and his father readied a stretcher that would carry Ahliddin through the Pamirs to Afghanistan, where they would spend the winter in a camp along with thousands of other Tajik refugees. His youngest brother, Rahmiddin, then six, also came. Umarov does not know which pass they took. He only remembers the snow.

By springtime, Ahliddin had a new leg from the Red Cross, but the boys needed a new home. "The Taliban were not in Afghanistan at that time," Umarov says, "but the country was not peaceful either." Their father took them south to Pakistan, then returned to his wife and daughter in Alisurkhon. "We attended religious schools in Peshawar," Umarov says. "Our studies were paid for by wealthy Pakistanis and the government."

I ask what these schools taught about America, and he smiles knowingly. "Maybe there were schools with the primary goal of preparing fighters," he says, turning to face me, "but where I was, we never thought of these things. We were very young." He gestures to the wall. "I heard about America when I saw it on this map. But I didn't know anything about it."

He stayed for six years, moving through three schools. He learned Urdu, Pashto, and Arabic. He was a good student, and a good soccer player. In May 2001, soon after his graduation, the Tajik Embassy gave him a passport and documents for a trip home to newly stable Tajikistan. He returned proudly to Alisurkhon—the eldest son, diploma in hand—and helped his parents with the harvest, collecting apples and potatoes and walnuts. "But then America started bombing Afghanistan," he says, "and the whole world went crazy."

That fall, Umarov was dispatched by his parents back to Pakistan, to raise enough money to bring his brothers home. With direct flights nonexistent, and the land route via Afghanistan treacherous, he flew via Iran. Once in Pakistan he worked selling clothing, food, and pencils—whatever was in demand—in the Peshawar bazaar, and on May 13, 2002, he decided to visit Karachi in search of a steadier job. A Tajik friend, Abdughaffor, had a place for him to stay.

Abdughaffor lived in a room in the University of Karachi library, where he worked. Also staying there was another Tajik, Mazharuddin, whose name means "place for the miraculous appearance of the faith." All four walls in the library were filled with books, and on the floor were thin carpets. The three Tajiks slept on the carpets. They hung up their T-shirts. It was early in the morning of May 19 when Pakistani secret service agents came. The agents woke them up, took the T-shirts down, and used them to tie the men's hands and cover their eyes.

When his blindfold was removed, Umarov was in a jail cell, his friends at his side. "I was not afraid," he says. "I knew I'd done nothing wrong." The Pakistanis took them one at a time for interrogations, quizzing them in rapid-fire Pashto about their names, birthplaces, and histories—and about a bombing that had just occurred. "Somewhere in Karachi," Umarov says, "there was an attack. A bomb exploded."

It had been Pakistan's first suicide bombing: Eleven days earlier, a red Toyota Corolla had pulled alongside a minibus outside the Karachi Sheraton, its tires screeching. An explosion ripped the bus apart, shattered nearby windows, and left a smoking crater in the ground. Three passersby and 11 passengers—French engineers working for the Pakistani navy—were killed. At least 22 others were injured. Pakistani authorities immediately suspected outsiders; newspapers ran ads asking the public to report any suspicious foreign nationals. (The investigation would, in fact, lead to a homegrown mastermind, Sohail Akhtar, alias Mustafa, who was eventually arrested in April 2004.)

After 10 days of interrogations, Umarov was handcuffed, taken from his friends, and driven across the city. He thought he would be freed; the Pakistanis had said as much. But the drive ended at a building that looked like a luggage factory—a secret jail where leather briefcases were stacked high against the walls.

Two Americans were running the jail, both blond, one with long hair, one short. One was a "strong man," big and muscular; the other had an average build. Neither wore a military uniform. "The reason I knew they were Americans," Umarov says, "is that they told me so." Later, he would hear that America paid bounties for suspected terrorists, and he would wonder if he, too, had been purchased.

No longer was he questioned about the Karachi bombing. The Americans interrogated him about Al Qaeda. "They asked me what I knew about the terrorists," he says. "Did I know where they were?" They asked if his passport was fake, and if he'd seen or met Osama bin Laden. "Of course, I'd heard about him on the radio and TV," Umarov says. "But how would I, a student, know much about him if people who came from a powerful country like America did not know anything about him?" He pauses and looks at Kubad and me, inviting us to question his logic.

"I was not afraid," he repeats. "I am not a thief—not someone who should be afraid of them or anything. I told them what I knew." If he lied, the men said, they would send him to Cuba. Umarov remembers turning to the translator. "What is Cuba?" he asked.

When the questions were over, they locked him in a concrete room for 10 days. The room was three feet long and one and a half feet wide and insufferably hot. He wore iron handcuffs. It was impossible to stand up or move about. "All my thoughts were about how my life was going to end," he says. He worried about his brother Ahliddin, about an unpaid debt to his neighbors, and about the times in his life when he had made people angry or upset. "When I wanted to go to the toilet," he says, "I would knock on the door and three guards—one with the gun and two with the stick—took me there." Three times a day, he was given a bowl of rice, one chapati, and one glass of tea.

"I was angry at these men for putting me in that room without any reason," he says. "But if you read the history of Islam, you will know there are stories similar to mine—when people are taken or sentenced to death without any reason. It taught us to keep our emotions together." What confused him was that there seemed to be no purpose to his treatment; it was not a tactic to get him to talk. The blond Americans did not interrogate him again. He was returned, bleary-eyed and unwashed, to the Pakistani jail, where his friends were still being held. "From my appearance," he says, "they knew I had not been in a good place."

At 2 a.m. the next day, the Pakistanis handcuffed Umarov, Abdughaffor, and Mazharuddin and put black bags over their heads. There was a bus, where American soldiers took their photographs, and then an airplane, where they were tied together on the floor. They wore metal belts around their waists and chains over their shoulders. They could not move, Umarov tells us. They did not know where they were going.

When the plane landed, two soldiers lifted them and counted, in English, "One, two, three," and threw them into a truck. "As a sack of potatoes," Umarov says. He landed on the metal truck bed. His friends landed on top of him. "When we cried out," he says, "we were kicked."

Umarov breaks from the storytelling and stands up, and Kubad and I follow him outside into the blinding daylight. Walnuts are spread out on a canvas tarp, drying in the sun. He plucks a handful of tiny red apples from a tree, presents them to us, and disappears through a door. When he returns, he's carrying a stack of papers: documents, in English and in Russian, from the Red Cross and the U.S. Department of Defense.

"This individual has been determined to pose no threat to the United States Armed Forces or its interests in Afghanistan," one reads. "There are no charges from the United States pending [sic] this individual at this time." It goes on: "The United States government intends that this person be fully rejoined with his family."

These papers are now the only form of identification Umarov has, he says—a red flag that causes shakedowns at Tajik checkpoints and occasional arrests. The U.S., which offered no compensation upon his release, never returned his passport either. Attempts to get a new one have been blocked by a local official—part of the "KGB," as Tajiks still call it—who also blocked Ahliddin's passport application and demands periodic bribes from the now vulnerable family.

An airplane hangar, vast and bright with artificial lights, was Umarov's third prison: Bagram, Afghanistan. "Our cages were in a two-story building inside the bigger building," he tells us. "They had high fences and were surrounded by sharp wires." All the windows were covered. "The whole place," he says, "was blocked from daylight and man's sight."

Each cell held as many as 15 men; each man was issued blue prison dungarees, a wooden platform to serve as a bed, and two blankets. Umarov used one of the blankets as a mattress, the other to cover himself—though it wasn't enough. The nights were cold, and the guards would not let him put his head under the covers. Inmates wore shackles on their wrists as well as their ankles, even when sleeping, and each was assigned a number. Umarov's was 75. "Seventy-five," he whispers in halting English. "Seventy-five, come here."

Powerful lights flooded the cages 24 hours a day, and the guards made loud noises to keep the prisoners awake. They hit their billy clubs against the metal fences. They pounded on barrels. They threw cans and empty water bottles. "We lost count of days, let alone dawn and dusk," he says. "We never saw daylight. We were never outside." Groups of four guards worked eight-hour shifts; black tape covered the names on their uniforms. One American looked just like Rambo: no uniform, a scarf on his head, a cut on his hand. "I know him," Umarov says, smiling. "He was the guy who made the film about Afghanistan."

If the prisoners talked to each other, the soldiers forced them to stand and hold their shackles above their heads until the pain made them not want to talk again. If they talked again, Umarov says, the soldiers would take them upstairs and beat them. He was never beaten. But once he dared to talk to Abdughaffor and Mazharuddin, and the soldiers forced him to stand for hours, holding his shackles up while his arms shook. He did not talk again.

Umarov knew the other men in his cage as faces. He grew bored of looking at them. They were Arabs and Afghans and Pakistanis and men who spoke French and English. These, he assumed, must be the terrorists—the ones to be blamed for the world going crazy, the ones who should be punished. Sometimes, when a cellmate was taken upstairs, screams would ring out across the prison. "This did not happen every day," he says, "but it happened."

I ask for details, and he's reluctant to say more. "I did not see anything with my own eyes," he says, "and my friends and I did not experience this torture." He pauses. There were stories he later heard in Cuba, he says—stories that he believed—about "beatings with the wooden stick" and electrocutions. "American soldiers used electrical cables to shock them in their eyes, hands, and feet. Three men told me this. And some, mostly Arabs, were forced to remove their clothes in front of women. There were other things, too." He will not go on.

I wonder if I should put any faith in rumors passed from detainee to detainee to me, then realize I'm missing the point. Umarov's story is best understood as what happens when an everyman is imprisoned without trial, moving through a system built for the worst of the worst. It's not a story about the cruelest cases of torture—those that America may someday expose and bemoan and ban—but about something that may be scarier: what has become normal in the war on terror.

In two months at Bagram, Umarov says, he had only one interrogation—with an American woman who questioned him in Farsi and seemed confused as to why he was there. "We were alone in the room," he says. "She checked my documents and listened to my answers, then told me I wasn't guilty." Life became a haze. He would stand and sit and try to sleep in his cage, and every fifth day a soldier loosened his handcuffs and let him walk around the prison grounds. Every seventh day, he was brought to the showers, which often had female guards and shut off after two minutes, even if he was still covered in soap.

One day early in August, while Umarov and his friends were eating lunch, the soldiers came to take them to Cuba. They walked into their cell and started shouting, "Stand up, stand up!" and everybody did, leaving plastic containers of pasta and meat half-eaten.

"They handcuffed our hands with metal," he says, "and covered our eyes with something like sunglasses, only it was impossible to see through them. They covered our ears with something like headphones, only it was impossible to hear anything." His mouth and nose were covered with tape, then with what seemed like a surgical mask. They placed a dark hood over his head, and it became difficult to breathe. They tied his legs and feet with a chain and attached this chain to another chain around his waist. Finally they marched him onto an airplane and chained him to the floor. "After that," he says, "I do not remember anything."

"I was sleepwalking when we came to Guantanamo," he tells us. "I did not understand where I was." He was unloaded from the airplane, but he does not recall how. "When my consciousness appeared," he says, "I found myself in the sandy desert. And I thought I would be executed there, in the desert." His wrists, legs, and face were bleeding from the shackles and mask. Soldiers loosened the cuffs and straps, changed the tape on his mouth, and removed the thing that blocked his ears. They took him to the showers and gave him a clean uniform—this time in orange—and a new number. Then Prisoner 729 went for an immediate medical checkup and interrogation.

At first, he was interrogated every week. "There were new investigators every time," he says. "There was a new room every time. But the questions were always the same"—an endless repetition of the conversation about Pakistan and Tajikistan and his life in both. Occasionally, he became so angry that he wouldn't answer their questions, preferring to sit in silence. Other times, he challenged his interrogators: "Why was I taken here if I have not committed any crimes?"

They told him they were suspicious because he had traveled many places, many times, by many routes. He had been to Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran. "I answered that they could find many people like me," he says. "Why was it that it had to be me?" They said that the routes he'd taken were famous, and used mostly by terrorists; he might have seen the terrorists on the roads. They asked if he'd known any of his fellow passengers on his flight to Iran. "The people on the plane were mostly American journalists," he responded. "Why not arrest them?"

At Guantanamo, the showers lasted five minutes. At first he had three showers a week, then he had four, and soon he had showers almost daily. The frequency of showers went up and the frequency of interrogations went down. They began calling him in only once a month, then once every two months. Eventually, they stopped interrogating him altogether.

"The hygiene was good in Cuba," he admits, "and we were allowed to pray and fast." Each cell had a Koran and a real bed, and, through a mesh fence, Umarov could talk freely with his neighbors. (Like other detainees, Umarov believes that staring through the mesh has permanently affected his vision.) He did not wear handcuffs in his cell. Those were used only during biweekly exercise sessions, when the guards chained his hands to his feet and led him shuffling around a fenced yard. After his walks, they always returned him to a different cell, and to different neighbors. He ended up near Mazharuddin once. He met his formerly silent cellmates from Bagram and a principal from Pakistan and a farmer from Afghanistan and an English-speaking Kuwaiti who liked to talk to the soldiers.

"Some men were moved constantly," he says. "They would wake them up, put them in chains, and take them to a new cell or to an interrogation room." Prisoners were left shackled in a standing position until the investigators arrived. "They sometimes had to stand for 24 hours, moving only when they were brought to the toilet," he says. "How could anyone be normal after that?" Yet Umarov never heard Bagram-like yells at Guantanamo, and few of his neighbors told him they had been tortured. What they talked about was injustice. "We did not know why we were there or when we would leave," he says. "At Guantanamo, the torture wasn't physical—it was psychological."

Some prisoners went insane. Abdughaffor was one of them. He would throw himself against the door and scream. He tried to hang himself. He wouldn't eat. He became somebody Umarov did not know. Others took off their clothes and sat naked in their cells. "These people became like children," he says. "They did not understand their reality."

"During the first five or six months," Umarov says, "I believed they would find the terrorists among us, take them away, and let the rest of us go home." But his detention continued. He lost hope. "I started to believe that America was against Islam," he says.

He did not see the soldier write slurs in the prisoner's Koran, but he believes that it happened—an Arab told him about it. "People did not mind when translators or those who believed in God touched the holy book," he says, "but they were angry with the faithless and godless soldiers who wrote ugly words inside it. Kafirs—godless people—are not allowed to touch the Koran." Rumors of a desecration swept through the prison. The next day, 10 prisoners attempted suicide; by week's end, there were 23 "hanging or strangulation attempts," according to the U.S. Army's Southern Command, which oversees Guantanamo.

Around Umarov, men tried to hang themselves using prison sheets, twisting there until soldiers came to cut them down. "I thought about it, too," he admits. "But from the Islamic point of view, suicide is a sin. We advised our neighbors not to do it." He witnessed one or two attempts a day. In response, the guards removed the sheets from the cells, turned off the water, and stripped every prisoner to a T-shirt and underpants.

Other prisoners, Umarov included, went on a hunger strike. Umarov joined this strike and two others, going days without food and water, not changing his clothes. "I wanted to either be sent back or die there," he says. The military eventually issued an apology over the loudspeakers. "They publicly apologized to us in different languages," he says. "It meant that we could stop." Soldiers came to haul them off to the camp hospital. In extreme cases, doctors came to the cells and stuck tubes into their arms.

"The American soldiers were like us in a way," he tells us. "They did whatever was ordered from the top—and they are not guilty for that." He watched as fellow prisoners told their stories to guards, and he watched as guards cried after hearing them. "We told them about Islam and how beautiful it is," he says. "Had they not been soldiers, I am sure they would have converted into one of us without questions."

Yet it is the soldiers whom Umarov blames for the worst of his days at Guantanamo. It was the first day of Ramadan, he recalls, when he decided to go above them and ask an investigator about his status. After his meeting with the investigator, the soldiers punished him for his insolence. They threw him into isolation for 10 days.

"I was taken to the dark room," he says. "The soldiers took all my clothes and left me there." The room was made of iron; it measured three feet by five feet. At night, frigid air was pumped through a hole in its ceiling, and its small window was covered by Plexiglas so the air couldn't leave. Two electric coils provided dim light, and during the day, they were turned up to heat the cell to a very high temperature. But night was worse. "Some prisoners wouldn't last the night and had to be taken to the doctor," he says. "They kept me there for 10 days—and for no reason."

He later spent another 15 days in isolation, but for that, he says, there was a reason. I ask him what it was. "I was standing in the cell block, leading a prayer for 48 people, and a female soldier came up and stood right next to me. I asked her to move, but she would not. She was doing psychological pressure. So I spit on her."

It is late in the evening now, after eight hours of interviews, and Umarov, Kubad, and I pause for dinner. Ahliddin brings in a meal of bread, boiled potatoes, and tomatoes. We eat with our hands.

I ask Umarov to demonstrate how he was chained during interrogations, and he rocks forward, crossing his ankles and tucking his arms underneath his knees. He does it automatically, almost unconsciously, then stares at me with a sickly smile. I press him for more information about the suicides, more about his time in the air-conditioned box. His smile fades.

"What I've already said should be enough for those who want to know about this prison," he says softly. "It was like being in a zoo, with people coming to stare and laugh at you." I keep pressing. His voice rises. "There is no point in telling more of these stories. Such a prison has never existed in the history of mankind. No one has ever written about such a prison. Why did they keep a man for two years with no reason? Why? They caught me and kept me as a prisoner of war. What war, may I ask? When was I involved? I was sleeping when they came and dragged me out of my bed. People who understand the laws will have already made up their minds about who is who."

Ahliddin tries to change the subject. "In Pakistan," he says, "I met a family that had lived in America. They'd worked as dog washers." He tries to say the words in En-glish: "dog wah sir." We keep eating, pondering the absurdity that, somewhere in the world, it could be a man's job to wash a dog. "That's what's wrong with America," Kubad announces. "When a dog is dirty, you think it's a problem. When a real problem comes, you don't know what to do."

In February 2004, Umarov played soccer again. He and dozens of others were moved to a new, lower-security prison camp within Guantanamo called Camp 4. The cells were bigger there and the food had taste, and they had meals together in a special room for eating. "We could walk and talk freely," he says. "If we didn't finish our food, we could keep it with us." He was reunited with Mazharuddin and Abdughaffor, who was now better. Better…though never again himself. No longer did they have to wear orange uniforms. This was an important thing. In Camp 4, the uniforms were white, almost like normal clothing. The prisoners were watched via closed-circuit cameras; they could spend six hours a day outside in the fresh air.

Umarov wasn't good at soccer anymore, but he was stronger than many of the others. Some had become too weak to run. "We were like two teams of old men," he says. "Worse than old men." They played every day.

In March, Umarov, Abdughaffor, Mazharuddin, and 13 others from Camp 4 were issued uniforms in yet another color: brown. They noticed a change in the way the soldiers treated them, and they started getting called in for interrogations again. Umarov had four in quick succession.

The last investigator he met was an old man, and he was brought to him free of chains. The investigator was tall, with gray hair and a belly, and he sat at a table that held candies, tea, and cans of Pepsi Cola. Umarov had never been offered Pepsi Cola during an interrogation before. He sat down at the table, and the investigator made a speech. "He told me that the main reason America had been fighting and bombing in Afghanistan was to get rid of terrorists and those who create chaos," Umarov says. "He said that in a war situation, there are always people who are affected who were not guilty. He felt sad that two years had been taken from my life, and that I'd been kept away from my family." Now Umarov would be freed.

The investigator advised Umarov to think of his future. If people approached him to fight against America, he should not join them. He should have a family and be a good father to his children. "He shared the story of his own life with me," Umarov says. "He was left without a father at a young age—that's why he was suggesting that I think about family." They spoke for nearly an hour. At the end, the investigator stood up and hugged him. Umarov imagined his mud room with the Soviet map, his parents, his orchard, his apples. He was not mad at this speech. He was happy.

At 2 a.m. on March 31, 2004, Muhibullo Abdulkarim Umarov, along with his two Tajik friends and a dozen others, walked without chains through a gauntlet of soldiers at the Guantanamo airfield. Journalists' flashes popped and cameras rolled as the procession of detainees passed, and two guards—a man and a woman—carefully helped Umarov board an airplane. Inside its belly, away from the journalists, they then handcuffed him and chained him down, and they covered his eyes with the same plastic glasses. They covered his ears with the headphones. They covered his mouth with tape. "But this time we were not chained to the floor," he says. "We were chained to the benches."

Radio interview:

05

Glaciers for Sale: a global warming get-rich-quick scheme

05

Glaciers for Sale: a global warming get-rich-quick scheme

Glaciers for Sale: a global warming get-rich-quick scheme

by McKenzie Funk

First published in Harper's Magazine, July 2013

The Canadian dentist behind what may or may not have been the world’s first global-warming Ponzi scheme either lives or does not live in Iceland. His name is Otto Spork, and when I first learned of him, in 2008, he had secured the water rights to a glacier north of Reykjavík and quit his dental practice to run the most successful hedge fund in Canada. His Toronto investment firm, Sextant Capital Management—the name was chosen to honor his paternal grandfather, Johan Marinus Spork, a Dutch sea captain—had recently been claiming 730 percent returns for its investors. Spork’s sales pitch was simple: the world was warming and parts of it were running dry, so Sextant bought water companies. Hundreds of Canadian and offshore investors were persuaded to buy in—and Spork earned millions of dollars in management fees as money poured into his funds. The arrangement succeeded magnificently until December 8, 2008, three days before Bernie Madoff was arrested, when the Ontario Securities Commission accused Spork of a massive fraud.

Water is the medium of climate change—the ice that melts, the seas that rise, the vapor that warms, the rain that falls torrentially or not at all. It is also an early indicator of how humanity may respond to climate change: by financializing it. In the year following the release of Al Gore’s 2006 documentary An Inconvenient Truth, at least fifteen water-focused mutual funds were created. The amount of money controlled by such funds ballooned from $1.2 billion in 2005 to $13 billion in 2007. Credit Suisse, UBS, and Goldman Sachs hired dedicated water analysts. A report from Goldman called water “the petroleum for the next century” and speculated excitedly about the impact of “major multi-year droughts” in Australia and the American West. “At the risk of being alarmist,” it read, “we see parallels with…Malthusian economics.”